By Ken Johnson

John Muir was one of the most significant environmentalists in U.S. history and the world. He was instrumental in establishing Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks and the Petrified Forest National Monument (now a National Park) and helped found the Sierra Club. Muir was influential in making the preservation of our national lands a focus of congressmen and presidents. He was an advisor to President Theodore Roosevelt who traveled to Yosemite to camp with Muir and seek his counsel.

John Muir was one of the most significant environmentalists in U.S. history and the world. He was instrumental in establishing Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks and the Petrified Forest National Monument (now a National Park) and helped found the Sierra Club. Muir was influential in making the preservation of our national lands a focus of congressmen and presidents. He was an advisor to President Theodore Roosevelt who traveled to Yosemite to camp with Muir and seek his counsel.

Born in Scotland in 1838, young John Muir moved with his family to Wisconsin in 1849. He took college courses in botany and chemistry at the University of Wisconsin- Madison and became deeply interested in the natural world, an interest that would be the focus of his life. After leaving college and Wisconsin, Muir spent several years in Ontario, Canada, working in a combination sawmill and rake factory.

In 1866, he moved to Indianapolis where he worked in a wagon wheel factory. The following year, he severely injured his right eye in an industrial accident and was blind in both eyes for a time. Despite this serious injury, he regained his sight and was determined to make a journey which would change his life and ultimately would set him on a course to change the country.

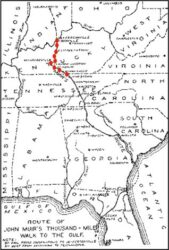

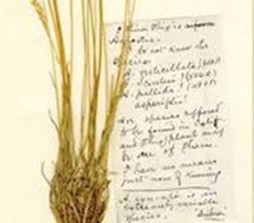

John Muir decided to take a walk. A very, very long walk. Ultimately 1,000 miles from Louisville to the Gulf of Mexico. He began his walk on September 2, 1867. He walked through Louisville without speaking to anyone and headed south. Muir traveled light, carrying only a backpack with his journal, a change of underwear, the poems of Robert Burns, Milton’s Paradise Lost, a botanical plant press to preserve the specimens he gathered, some toiletries, and a map. After leaving the Louisville area, he spread out that map and planned his journey. Muir’s journal of this trip was edited in 1916 by William Frederic Badé and published as A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf.

John Muir decided to take a walk. A very, very long walk. Ultimately 1,000 miles from Louisville to the Gulf of Mexico. He began his walk on September 2, 1867. He walked through Louisville without speaking to anyone and headed south. Muir traveled light, carrying only a backpack with his journal, a change of underwear, the poems of Robert Burns, Milton’s Paradise Lost, a botanical plant press to preserve the specimens he gathered, some toiletries, and a map. After leaving the Louisville area, he spread out that map and planned his journey. Muir’s journal of this trip was edited in 1916 by William Frederic Badé and published as A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf.

Taking clues from that book and with modern maps of the state, I traced his route. I made the same trip through the Kentucky portion of his trip recently. My trip was significantly different as I traveled by automobile, but the hints from his journal were helpful and my journey closely followed his route.

Muir mentioned several towns he traveled through, but left out others, his focus always being on nature. It is almost certain that he started out following a portion of the old Wilderness Road and made his way through Gap in the Knob north of Shepherdsville. He did not specifically mention Shepherdsville, which was then a town of about 300 people, and it is likely that he skirted the town to the east, possibly along the route where I-65 is now. It is tempting to think that he may have gone far enough to the east to have walked on what is now Bernheim land, Unfortunately, nothing in his writing confirms that. With every step of his journey, Muir observed nature and looked for unfamiliar plant species to collect and study.

Muir spent the first night his walk in an old tavern. In the morning, he set out again, first crossing the Salt River which he described as nearly dry. From there, he may have followed what is now Kentucky Route 61 before adjusting his path to follow Horsefly Hollow Road until it joins Tunnel Hill Road and leads into Elizabethtown. While walking along that route, he traveled through what is now the southeastern portion of Fort Knox. There, he crossed the Rolling Fork near a small settlement. The stream was fast moving and he accepted the offer of assistance from some Black residents who saw his situation. In recent years, Muir’s great contributions have fallen under a shadow. His language and actions when dealing with People of Color have come under increasing scrutiny. This encounter was no exception and the language used in his journal, while commonplace in that time, is reprehensible. Like everyone, his failures must be considered as well as his great accomplishments.

After passing through Elizabethtown, Muir adjusted his course to walk nearly due south where the land was flatter and he was able to cover considerable ground as he traveled through the lightly forested Barrens Region. He slept that evening among some bushes near Sonora. The following day, he had one of the shorter walks of his journey. He traveled only ten miles and passed a stand of black oaks being cut for their lumber. Muir observed that Kentucky oaks were, “…the master existences of its exuberant forests. Here is the Eden. The paradise of oaks.” He stopped for the night at a tavern in a village that “seemed to be drawing its last breath.”

He continued his journey on September 5, following the general course of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad line noting several caves along the way. Stopping along the way, he took out his plant press to preserve the specimens he had collected.

In Munfordville, he met with a member of the Munford family who shared his interest, if not his knowledge, in nature and science. He made his way out of town and continued his southerly journey and stopped to spend the night in a log schoolhouse. On September 6, he rose with “the earliest bird song” and made his way to Horse Cave and then on to Mammoth Cave. He noted the microclimates near the cave entrances and the plants that grew there and made a short exploration of Mammoth Cave. He left the cave and continued his journey where he spent the night in the home of a hospitable farmer before traveling through Glasgow Junction (now Cave City).

September 7 found him back in hilly country, as he made his way to Glasgow, judging it to be one of the few towns in the South that showed signs of “ordinary American life.” He passed the night in the in the home of a well-to-do farmer. In the morning, he entered what he considered a grand landscape as he walked through Burkesville and admired the beauty of the Cumberland River and spent the night on a hillside under the stars. September 9 would find him departing Kentucky as he crossed the border into Tennessee.

John Muir’s journey on foot through Kentucky was about 175 miles. The convenience of modern travel allowed me to drive that route and return home by early evening of the same day. Muir spent 7 days in Kentucky and averaged 25 miles of walking per day. His journey would continue for over 800 more miles and end about 10 weeks later in the Cedar Keys in Florida, when he was stricken with malaria. He recovered and went on to have many more journeys and discoveries and to become a leader in the effort to preserve America’s wild areas.

Muir had fine memories of Kentucky “How shall I ever tell of the miles and miles of beauty that have been flowing into me in such measure? Those lofty curving ranks of lobing, swelling hills, these concealed valleys of fathomless verdure, and these lordly trees . . . these are cut into my memory to go with me forever.”

If John Muir’s travels didn’t take him through Bernheim, the words above still describe it perfectly. Come to the forest, make your own discoveries, make your own memories.

The full text of Muir’s journey as edited by William Badè is available online at A Thousand Mile walk to the Gulf by John Muir – Project Gutenberg. In 201,7 Andrew Berry, Bernheim’s Director of Conservation, celebrated the 150th anniversary of Muir’s walk with his own walk through Bernheim. See the archived posts here. Following Muir’s death in 1914, President Roosevelt wrote “He was emphatically a good citizen . . . a man able to influence contemporary thought and actions on the subjects to which he had devoted his life.”