By Andrew Berry

Muir awakens in a rickety tavern on September 3, 1867 and begins his journey south towards the Salt River.

“Escaped from the dust and squalor of my garret bedroom to the glorious forest. All the streams that I tasted hereabouts are salty and so are the wells. Salt River was nearly dry.”

Next Muir encounters the cedar glades, areas where limestone bedrock is on the surface and vegetation is sparse. These expanses of cedar glades lie just north of Bernheim Forest.

“Much of my way this forenoon was over naked limestone.”

Muir soon encounters the knobs. We know he went east of Indian Knob, visible directly across from western end of highway 245. This route follows the present day Interstate 65 corridor.

“After passing the level ground that extended twenty-five or thirty miles from the river I came to a region of rolling hills called Kentucky Knobs — hills of denudation covered with trees to the top. Some of them have a few pines.”

‘Hills of denudation’ refers to the weathered shape of the knobs, a geological term for hills formed by erosion of a plateau, rather than those formed by uplift.

Distances from ‘the river’ likely refer to distance from Ohio River. Muir notes 25 to 30 miles of river bottom. It is 25 miles from the Falls of the Ohio to the Indian Knob – Bernheim Forest area where the knobs truly begin.

Muir soon encounters brambles and vines, the thick vegetation that covers the landscape in early September. His rambling nature may have included a trip down Poor Farm Road, now presently known as Highway 245.

“For a few hours I followed the farmers’ paths, but soon wandered away from roads and encountered many a tribe of twisted vines difficult to pass.”

“Emerging about noon from a grove of giant sunflowers, I found myself on the brink of a tumbling rocky stream [Rolling Fork].”

Muir complements the verdant nature of Kentucky in September. It would seem to be wet year, although Muir does note that the Salt River is nearly dry.

“Kentucky is the greenest, leafiest State I have yet seen. The sea of soft temperate plant-green is deepest here.”

“Far the grandest of all Kentucky plants are her noble oaks. They are the master existences of her exuberant forests. Here is the Eden, the paradise of oaks.”

In 1867 the great virgin forests of the Knobs were falling to the axe. They were first used as fuel for salt production, later for iron furnaces, lumber, and charcoal.

“Passed gangs of woodmen engaged and hewing the grand oaks for market. Fruit very abundant. Magnificent flowing hill scenery all afternoon. Walked southeast from Elizabethtown till wearied and lay down in the bushes by guess.”

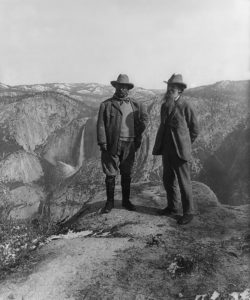

From here Muir hiked south to Mammoth Cave, and on to the Gulf of Mexico, where he caught a ship to Cuba. Within a few months Muir travels to California where he arrived in Yosemite for the first time in 1868. He would spend the rest of his life out west, eventually leading efforts for Yosemite to become a National Park in 1890, and to create and serve as founding President for the Sierra Club in 1892. His legacy may have largely formed during his later years in California, but his enthusiasm for the natural world and environmental ethics were cultivated during his hike through Kentucky in 1867.

Want to learn more? Read the previous two blogs to learn the background and to tell more of Muir’s story in his own words.

Sunday, we will have a live tweet of our Forest Manager, Andrew Berry’s hike through the forest.

UPDATE: Follow the live tweet on Twitter (@bernheimforest) or see the recap here.