By Ken Johnson

One of the many joys of visiting Bernheim Forest is seeing the healthy population of resident deer. They roam freely throughout our 16,137 acres and the most frequent sightings take place in early morning or in the evening in the arboretum where they are often seen grazing on the grass and other vegetation. The whitetail deer, Odocoileus virginianus, is very common in the area and throughout the state, but it hasn’t always been that way.

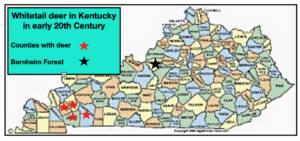

In 1928, when Isaac Wolfe Bernheim bought the land that became this forest, there were no white-tailed deer on it, nor were there any in the area and very few in the state. Unrestricted hunting in Kentucky throughout the 1800s had resulted in the near elimination of deer in Kentucky, though small populations still existed in isolated areas. An estimated 1,000 deer remained in Caldwell, Trigg, Crittendon, and Lyon counties. The first law to attempt to regulate deer hunting in Kentucky was passed in 1894 and forbid hunting from March 1 through September 1 but had negligible impact as no agency existed to enforce it. In 1912, the Kentucky Game Commission (now the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources) was created by the legislature. One of its first acts was to outlaw all deer hunting, a policy that remained in effect for over three decades.

The move to reintroduce deer throughout Kentucky had its start right here at Bernheim Forest. In 1930, in cooperation with the Department of Fish and Wildlife, a total of 54 deer were released in the forest. Over the years, that population has increased dramatically. Deer are now abundant throughout the area as the descendants of the Bernheim deer have spread far beyond the forest. Years later, the Kentucky Game Commission reintroduced white-tailed deer to game preserves in Christian, Crittendon, Livingston, and Ballard counties. Subsequent reintroductions would result in a healthy population throughout the state.

However, deer at Bernheim rapidly became a serious problem. The Game Commission had not only stocked Bernheim with white-tailed deer but also with European red deer, Cervus Cervidae, which were purchased from the Owensboro Park Commission. The number of red deer obtained is unknown but is thought to be at least fifteen. The European red deer are not closely related to the white-tailed deer and are approximately twice the size – close to the size of the American elk. The red deer found the knobs of Bernheim to be greatly to their liking and, with few predators, their numbers rapidly increased.

Unlike the native white-tailed deer, which can often be seen in small family groups, the red deer travelled in herds. It was not unusual to see 20-30 in a group. Some reports identify herds of 65 or more. They had definite dining favorites like the terminal buds of young conifers in particular. Scots pine, loblolly pine, red pine and others that were being grown in the arboretum to be transplanted throughout the forest were all badly damaged. The destruction continued for many years. The nursery area was fenced in to reduce the damage, but it was impossible for the young trees to be transplanted in the forest with any hope of success.

Red deer had a fondness for garden crops grown at nearby homes and farms that attention was not appreciated by Bernheim’s neighbors. The deer roamed over an area that stretched at least from Cox’s Creek to the east and Fort Knox to the west.

Within a half dozen years the problem had gotten to the point that something needed to be done. saac Bernheim, then living in Denver, Colorado, was getting reports of problems and he was demanding action. Unfortunately, there were no easy answers. Because of the agreement with the Game Commission, the Bernheim Foundation lacked the power to establish a hunting season or to selectively reduce the population by any means. Some of the proposed solutions now seem so improbable as to be absurd. One suggestion was to relocate all of the deer to the 4,000-acre portion of Bernheim Forest located in Nelson County usually referred to as the South Block.

Another idea was to herd all the deer to Fort Knox, or even to Mammoth Cave. Deer, both white-tailed and European, do not care to be herded anywhere they don’t care to go. Capturing them and transporting them somewhere was slightly more reasonable than other ideas, but only slightly. At that time, Bernheim had six employees, one tractor, and six horses. The Game Commission was not interested or equipped to assist. There was no fencing anywhere on Bernheim or Fort Knox that would prevent the deer from moving on. That idea was abandoned, the deer stayed and multiplied, continuing to be a major problem.

Finally, in 1946, Kentucky declared a hunting season for deer on Bernheim Forest, the first legal hunt in the state since 1912. A second hunting season was held later the same year. Other deer hunting seasons followed in the years to come. All achieved some success, but the red deer were able to recover each time and the population continued to rise as did the difficulties they caused for the development of the forest and the arboretum.

A solution was finally found and implemented in 1963. A 7’ fence was erected around the arboretum area to create a barrier from the natural forested areas at Bernheim. Denied their buffet of young trees in the nursery and arboretum the red deer looked elsewhere to forage. This made them vulnerable to being hit by traffic on the surrounding roadways and being poached. The last of the red deer soon were eliminated. The white-tailed deer have continued to thrive and are an important part of the ecosystem of Bernheim Forest and the rest of Kentucky. Visit Bernheim, and maybe you will be fortunate enough to catch a glimpse of one of these beautiful residents.