On some days, Schroeder manages her husband’s dental practice in Bardstown, a half-hour drive from Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest in Clermont, Kentucky. On other days, she is one of Kentucky’s most dedicated amateur malacologists (someone who studies mollusks). Schroeder’s specialty is land snails, humble gastropods that ooze around dirt and mud, feeding on algae and inseminating each other. It took Schroeder six years of unflagging effort to find a living hidden springsnail in Bernheim, but she managed to pull it off. Bernheim, which is held in a trust, is the largest privately owned nature reserve in the state and hosts various research efforts and 250,000 visitors a year. Schroeder’s discovery there could help protect the forest from the looming threat of a gas pipeline and road that could slice up the 16,137 acres of its ecosystem. But first, the snail.

Schroeder’s love of mollusks sparked when she was 16. She had just stopped in a rock and fossil shop in Columbus, Ohio, which got her hooked on seashells. “But it’s a long way from Kentucky to the nearest beach,” she writes in an email. “So I gradually shifted my interest to land snails.” In 2008, she started a one-year survey of Bernheim for land snails and soon created the Bernheim Land Snail Inventory, which now includes 80 species. In May 2019, the hidden springsnail became the latest to join the list.

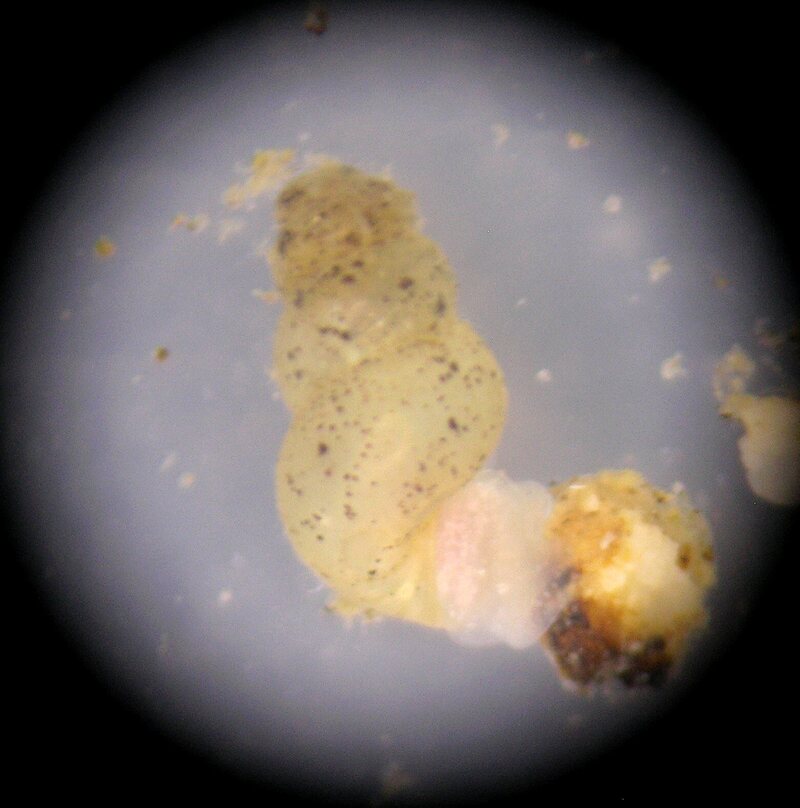

Before this discovery, the hidden springsnail, or Fontigens cryptica, had only been found in five other places in the world. It’s what’s known as a micromollusk, the blanket term for any incredibly small adult shelled mollusk. Micromollusks such as the springsnail have the unique blessing (or curse) or living their whole lives entirely unnoticed by the naked human eye. They’re too small be spotted easily even by dedicated beachcombers and conchologists—people who spend their lives in pursuit of shells.

As one might imagine, it’s no easy feat to spot a nearly invisible snail smaller than a grain of rice in a wriggling handful of loam. So Schroeder refined a strategy that is perhaps best described as sorting through trash. She gathers enormous bags of leaf litter, soil, and silt after spring floods and dries it out over the course of several weeks. She then shakes the dry material through a series of increasingly fine sieves before finally sorting through it with tweezers under a microscope. “The whole process can take many months,” she says. “I don’t know of a lot of people who have that sort of patience.”

Schroeder found her first springsnail shell in 2013 during one of her routine surveys of the Bernheim forest. She’d just excavated storm debris from Harrison Creek, which runs through Bernheim, and sifted a whole heap to isolate a handful of itty-bitty, empty shells that she couldn’t identify. She then emailed a photo to Rob Dillon—formerly of the College of Charleston and head of the Freshwater Gastropods of North America project.

Dillon immediately recognized them as Fontigens, but they seemed to be unusual. They could be from the most common species, F. nickliniana, he surmised, but the shells had a distinctively flat nuclear whorl. It didn’t look quite right. To make a correct identification, he told her, he’d need a living specimen.

Dillon instructed Schroeder to examine one of the coldwater springs near where she found the shells. A spring like that would likely be teeming with watercress, with springsnails on every leaf. He also advised Schroeder to bring a large water bottle for the copious collecting she was about to do. But Schroeder soon discovered that the spring held no watercress and, more importantly, no springsnails.

Schroeder was undeterred. She surveyed every single spring, cave, and hole in the ground near where she had found Fontigens shells. She skimmed the offshoots of culverts draining into creeks. No one had ever identified Fontigens of any species in Kentucky, but she soon uncovered more empty Fontigens shells, a sign that live springsnails were around somewhere. “I cannot remember ever witnessing, firsthand or second, a more earnest or comprehensive survey of any patch of the Earth for any mollusk population, of land or sea,” Dillon wrote in a post on Freshwater Gastropods of North America.

Rather fittingly for a snail too small for a human to see, F. cryptica only lives in caves too small for a human to notice, much less explore. In 1963, Hubricht had first located the snail in a spring in southern Indiana, in a cavity no larger than a fist. And despite her many searches, Schroeder found no trace of Fontigens in the larger caves that speckle Bernheim. Unlike most other species in the genus, F. crypticaappears to prefer the most liminal of spaces, “not surface springs, nor caves, but subterranean interstitial spaces,” Dillon writes in an email. It’s not a scale that’s friendly to human examination. So if a person does ever spot a springsnail, it’s most likely because it wandered off and got lost, according to Bernheim director of conservation Andrew Berry. “It’s a perfect storm of finding one that’s gotten so close to the edge,” he says.

Finally, on May 24, 2019, Schroeder’s luck changed. Along with her husband and Berry, she had trekked out to a spring in a previously unexamined valley in Bernheim, the Cedar Grove Tract. The tract contains Cedar Creek, a clear, ice-cold stream. There, she followed Dillon’s advice: find a decent-sized rock at the springhead and look underneath. Lo—there, under a decent-sized rock, Schroeder found a single, living, breathing specimen of F. cryptica. The tiny snail was just as ghostly white as Hubricht had described it in 1963.

“It’s what we would call one of the biggest biological finds in the history of Bernheim,” Berry says.

Though the hidden springsnail is not technically endangered, it’s uncommon enough that Berry plans to count it among other rare species found in Bernheim—such as the endangered bluff vertigo snail (also found by Schroeder) and the endangered Indiana bat—to make the argument that the forest is unique and worthy of further protections. The area is, Berry argues, part of the fabric and identity of the state. It was founded 90 years ago, when German immigrant and local distiller Isaac W. Bernheim purchased land that had been decimated by the iron ore industry. Following a plan created by the firm of famed park designer Frederick Law Olmsted, the forest was rehabilitated to realize Bernheim’s vision as a gift to the people of the state. That Bernheim has its roots in the distilling industry is fitting. “Kentucky is known really for the bourbon industry and traditionally the bourbon industry used these clean springs for production of their product,” Berry says. “So we want to protect the springs like the one at Cedar Creek.”

But it will be an uphill battle. The utility company Louisville Gas & Electric (LG&E) is forging ahead plans for a 12-mile natural gas pipeline that would run three-quarters of a mile through Bernheim’s forest. It would slice through streams, wetlands, and the coldwater springs and potentially contaminate the aquifer that supplies the springs. To date, LG&E has secured 85 percent of the easements required for the pipeline, though several landowners refuse to sell, including Bernheim forest.

Because of the terms of its purchase, Bernheim is legally prohibited from transferring its land for any purpose other than conservation. But LG&E, seemingly unbothered by this , plans to sue all reluctant landowners in the way of the pipeline. But LG&E still needs approval from government agencies, such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, according to local radio station WFPL. The Corps will conduct an environmental study to ascertain if the pipeline’s proposed pathway would threaten any rare, threatened, or federally endangered species in Bernheim. And that is where the hidden springsnail might come in.

But Berry doesn’t have high hopes for this survey. Instead, he’s asking for a full environmental and cultural study to give everyone a clearer picture of just how much is at stake. “They’re at least a year out from trying to roll bulldozers out and knocking down trees, but Bernheim’s not going to roll over on this,” he says. “This land is too much of a treasure.”

Meanwhile, the indefatigable Schroeder continues to sift through big bags of dirt and debris for Kentucky’s most mysterious little snails. She hopes to find more living specimens of F. cryptica to aid Dillon’s research on the evolution of cave animals, and to advocate for Bernheim’s future as a nature reserve riddled with tiny springs and tiny snails. “The night before our successful expedition, in late May, I said to my husband, ‘Tomorrow, we’re going to change the world,’” Schroeder says. “And maybe, in just a tiny little way, we did.”